Across the United States, campaigns to remove or restrict books about LGBTQ lives, especially transgender experiences, have accelerated in recent years. National tracking shows thousands of titles challenged or pulled from school and public libraries, with a disproportionate share featuring LGBTQ characters and themes. These efforts echo an older history of suppressing gender and sexuality research, most infamously when the Nazi regime looted Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science and burned its archives in 1933. Today’s book bans are not bonfires in the street, but the playbook is familiar: stigmatize a community, erase its knowledge, and narrow what the public is allowed to read.

This article explains what modern bans look like, how they spread, the legal guardrails that limit government censorship, what history teaches about erasing queer knowledge, and why inclusive shelves matter for young people and the health of our civic life.

What “Book Bans” Look Like Now

Modern bans rarely use the word “ban.” Policies are framed as relocating “age-inappropriate” content, limiting interlibrary loans, or creating challenge processes that let a small group remove dozens or hundreds of titles from access. National data shows just how widespread these actions have become:

- The American Library Association (ALA) recorded 821 attempts to censor library materials in 2024, challenging 2,452 unique titles across public and school libraries. While that is down from 2023’s record, it remains far above pre-2020 levels and continues a multi-year surge.

- PEN America documents thousands of bans each school year and finds that a large share target LGBTQ content. In 2023–2024, 29% of banned titles included LGBTQ characters or themes, and of those, 28% featured transgender or gender-nonconforming characters.

These numbers aren’t happening in a vacuum. Organized lists circulate online; model policies are introduced at the county or district level; and a handful of complaints can ripple out into large-scale removals. Reporters have traced waves of challenges that sweep entire collections, not isolated books.

Why LGBTQ and Transgender Titles Are Targeted

Censors often claim they are protecting children from “obscenity.” But professional library groups have repeatedly noted that many targeted books are not obscene by any legal standard; they are simply about LGBTQ people or address racism and identity. The ALA’s “Top 10 Most Challenged Books” lists and annual reports consistently cite LGBTQ content as a leading reason for challenges.

PEN America’s school-ban analyses show the pattern clearly: titles by and about LGBTQ people and people of color are disproportionately removed. That narrowing of the shelf is not viewpoint neutral. It strategically erases particular identities from public spaces that are supposed to serve everyone.

What the Law Says: Libraries, Students, and the First Amendment

Public libraries and public schools are government actors. That means the Constitution limits their ability to suppress ideas they dislike.

- Island Trees School District v. Pico (1982). In the leading Supreme Court case on school library removals, a fractured Court held that the First Amendment places limits on a school board’s discretion to remove books simply because officials disagree with their ideas. Students have a right to receive information; viewpoint-based purges run into constitutional trouble.

- Llano County, Texas (2023–2024). When a Texas county removed titles on race and LGBTQ topics from its public libraries, a federal district judge ordered books returned while the case proceeded. In 2024, the Fifth Circuit affirmed an injunction in part, requiring the county to restore access to several titles as the First Amendment suit moves forward.

- Arkansas Act 372 (2023–2025). Arkansas passed a law that threatened librarians and booksellers with criminal penalties for providing materials deemed “harmful to minors” and forced new challenge procedures. Federal courts blocked and later permanently enjoined key provisions as unconstitutional, citing vagueness, overbreadth, and the chilling effect on lawful speech.

The legal thread running through these cases is straightforward: government can set reasonable time, place, and manner rules and ensure truly obscene material is not distributed to minors, but it cannot target ideas or identities for suppression simply because some officials or residents disapprove.

A Hard Lesson From History: Burning the Archive

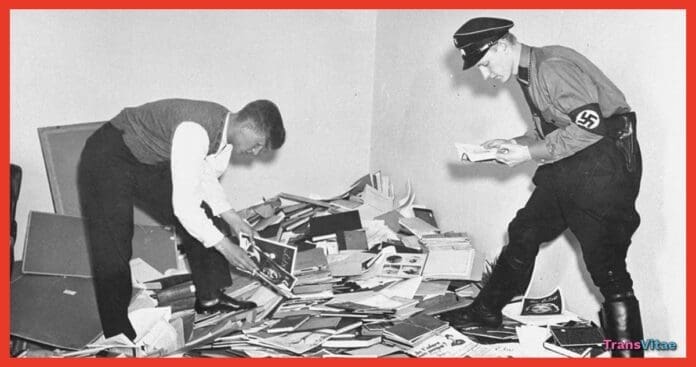

On May 6, 1933, Nazi students and paramilitaries raided Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin, an international center for research on sex and gender that had pioneered understanding of transgender people and hosted some of the earliest gender-affirming medical work. Days later, in the infamous book-burning ceremonies, they destroyed tens of thousands of books and research files as “un-German.” The Institute never recovered; Hirschfeld died in exile in 1935.

No one is equating modern U.S. policy debates with the enormities of the Nazi regime. The point is historical: regimes that seek social control often begin by attacking knowledge, especially knowledge about marginalized groups. Erasing records and stories makes it easier to erase people from public life. The images of Institute archives in flames are a stark reminder of what is lost when research and representation are treated as threats.

Why Inclusive Shelves Matter for Young People

Libraries are more than warehouses. They are public institutions of learning with a professional ethic grounded in the ALA’s Library Bill of Rights, which affirms that a person’s right to use a library must not be denied or abridged based on origin, age, background, or views, and that collections should represent all points of view.

A growing body of data shows why representation matters. The Trevor Project’s national surveys report that LGBTQ youth who have access to affirming homes, schools, community events, and online spaces report lower rates of attempting suicide compared to those who do not. While a library is not a clinic, it is a public space where seeing your identity treated as normal and worthy can be one of those “affirming spaces.”

When libraries purge LGBTQ titles, young people get a different message: your story is controversial, your identity is unsuitable for public shelves, and your existence must be hidden. That stigma has real-world mental-health consequences, even if it is not the only factor that queer and trans youth face.

The Practical Problems With Bans

Even setting aside constitutional and ethical concerns, bans create operational and community headaches that librarians and local officials know well:

- They chill lawful speech. Vague standards and criminal penalties lead staff to over-remove to avoid risk. Courts striking down Arkansas’s Act 372 highlighted exactly that problem.

- They shift power away from professional judgment. Selection and weeding policies are supposed to be guided by educational and collection-development standards, not political litmus tests. The Library Bill of Rights and its interpretations explicitly caution against prejudicial labeling and viewpoint-based restrictions.

- They invite costly litigation. From Llano County to statewide statutes, bans trigger lawsuits that drain public funds and time.

- They degrade information literacy. When certain perspectives on identity are scrubbed, communities get a narrower understanding of the world. Libraries exist to counter exactly that by offering broad, viewpoint-diverse collections.

“Age Appropriate” Without Erasure

Parents and guardians absolutely have a role in guiding their own children’s reading. Nothing in the Library Bill of Rights or professional practice denies that. The question is whether one set of parents should dictate everyone’s options. Libraries already use a range of tools to help families make choices without suppressing ideas for the community at large: reader advisory services, content descriptions, shelving by age level, and opt-in tools for parental oversight. Those are different in kind from blanket removals or policies that single out LGBTQ themes for unique restrictions.

Lessons From the Courts: What Works, What Doesn’t

- Content-neutral processes that evaluate books against educational and collection-development criteria, with transparent review and appeals, are more likely to be upheld.

- Viewpoint-based purges rooted in disagreement with ideas about race, gender, or sexuality collide with the First Amendment, as the Pico plurality and multiple federal decisions since have emphasized.

- Criminalizing librarians for making good-faith professional decisions is constitutionally suspect and practically harmful, as federal courts in Arkansas concluded.

The Stakes: Community Health and Democratic Culture

The health of a pluralistic democracy depends on people being able to seek and receive information. That principle is older than the internet and broader than any single identity group. Libraries are among the most trusted public institutions precisely because they welcome everyone and curate collections for the whole community.

When LGBTQ and transgender stories are targeted, the harm is specific and concrete; youth lose mirrors, families lose guides, and the broader public loses opportunities to learn and empathize. But the harm is also general. If elected officials can scrub identities they dislike from shelves, there is no stable principle stopping them from erasing other inconvenient histories or viewpoints next.

History warns us that suppressing knowledge about gender and sexuality does not make reality go away. It only blinds us, turning neighbors into strangers and policy into fear. The bonfires of 1933 destroyed irreplaceable research and lives; we honor that loss by refusing smaller erasures in our own time.

What Communities Can Do

- Know your policies. Read your library’s collection-development and reconsideration policies and insist they follow professional standards and the Library Bill of Rights.

- Show up. Library boards and school boards respond to who is in the room. Attend meetings, submit comments, and support staff.

- Support legal defense. When unconstitutional bans appear, they are often defeated because patrons, authors, and librarians bring suits, such as in Texas and Arkansas.

- Build affirming spaces. Schools, community groups, and families can help create environments where queer and trans youth see themselves included, which is associated with lower suicide risk. Libraries are part of that ecosystem.

The Bottom Line

Book bans that single out LGBTQ and transgender stories are not just about shelves. They are about who counts, whose lives are sayable in public, and whether government can put a thumb on the scale of identity. The law sets limits on that power. History shows the cost when we ignore them. And the data tells us that inclusive, affirming spaces help young people thrive. Protecting the freedom to read is not an abstraction. It is a concrete, local choice communities make, one policy at a time, about the kind of future they want to build.