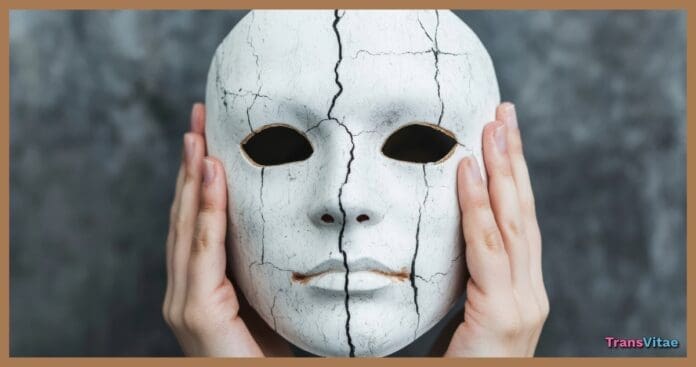

Emotional masking is one of the least discussed survival skills in the transgender community, despite how common it is. Many trans people learn early how to manage their emotional expression in ways that reduce scrutiny, conflict, or danger. Over time, this skill becomes so ingrained that it is often mistaken for personality, maturity, or emotional strength.

Masking is not about deception. It is about adaptation. It develops in response to social pressure, misgendering, rejection, and the ongoing need to assess whether authenticity is safe in a given moment. While emotional masking can be protective, it also carries long-term consequences that are rarely acknowledged.

Understanding why trans people become so adept at emotional masking requires looking beyond individual behavior and examining the environments that make such adaptation necessary.

How Emotional Masking Develops

For many transgender people, emotional masking begins long before they have language for gender identity. Childhood is often where the first lessons are learned about which emotions are acceptable and which are not. Children quickly notice when sadness, anger, or confusion is met with discomfort, correction, or dismissal.

When a child already feels out of place due to gender nonconformity or unexplained dysphoria, emotional expression can feel especially risky. The message may not be explicit, but it is consistently reinforced: certain reactions create problems, while emotional restraint keeps things calm.

As a result, many trans people grow up learning to regulate themselves tightly. They become careful with tone, facial expression, and emotional disclosure. What begins as situational awareness gradually becomes habitual behavior.

By adulthood, emotional masking often feels automatic rather than intentional.

The Relationship Between Gender Dysphoria and Emotional Control

Gender dysphoria does not exist in isolation. It often intersects with social expectations, gender roles, and assumptions about behavior. When a person’s outward presentation does not align with how they are perceived, emotional expression can attract additional scrutiny.

Many trans people learn that expressing frustration or distress risks being interpreted through stereotypes. Emotions may be dismissed as confusion, instability, or attention-seeking rather than legitimate responses to lived experience.

As a result, emotional restraint becomes a way to maintain credibility. Staying calm and measured feels safer than expressing pain that might be questioned or minimized. Over time, this reinforces the belief that being emotionally neutral is a requirement for being taken seriously.

This dynamic is especially pronounced in professional, medical, and institutional settings, where trans people are often expected to demonstrate composure in situations that would understandably provoke strong emotional reactions.

When Masking Is Rewarded

One of the reasons emotional masking persists is that it is frequently rewarded. Trans people who remain calm in difficult situations are often praised for being resilient, articulate, or strong. While these traits are not inherently negative, the praise can obscure the effort required to maintain emotional control.

When composure is valued more than authenticity, masking becomes a condition for acceptance. The trans person who manages discomfort quietly is seen as easier to support than the one who expresses anger, grief, or exhaustion.

This pattern reinforces the idea that emotional containment is a virtue, while visible distress is a liability. Over time, many trans people internalize this expectation and apply it even in situations where safety is not at risk.

A Personal Reflection

For much of my life, I was described as “easy to talk to” and “very composed.” Those labels were usually offered as compliments, and for a long time, I accepted them without question. I believed that emotional control was simply part of who I was.

What I did not recognize at the time was how much emotional editing was happening beneath the surface. I learned to soften reactions, redirect conversations, and minimize my own discomfort to keep interactions smooth. I told myself that this was maturity or professionalism, but it was also self-protection.

There were many moments when I felt deeply unsettled, frustrated, or hurt, yet responded with reassurance instead. Masking made life easier in the short term, but it also meant that my emotional needs were rarely visible, even to people who cared about me.

It took time to realize that being perceived as “fine” often meant that no one thought to ask if I actually was.

Hypervigilance and Emotional Masking

Emotional masking is closely connected to hypervigilance. Many trans people develop a heightened awareness of their surroundings and social dynamics as a result of past experiences. This awareness is not irrational. It is based on pattern recognition.

Hypervigilance involves continuously scanning for signs of safety or threat. Tone of voice, body language, and subtle shifts in behavior are all monitored, often unconsciously. Emotional expression is adjusted accordingly.

While this level of awareness can prevent harm, it also keeps the nervous system in a state of readiness. Over time, this can contribute to chronic stress, anxiety, and emotional fatigue.

Masking allows a person to navigate uncertain environments, but it also limits opportunities for genuine rest and emotional release.

The Long-Term Cost of Emotional Masking

When emotional masking becomes habitual, it can interfere with self-awareness. Some trans people struggle to identify their own feelings after years of suppressing or reshaping them for external consumption. Others minimize distress to the point where they no longer recognize when they are overwhelmed.

This disconnection doesn’t only affect negative emotions. Joy, excitement, and satisfaction can also feel muted when emotional expression is tightly regulated.

Masking can also impact relationships. When a person consistently presents as capable and unaffected, others may assume that support is unnecessary. This can lead to isolation, even within otherwise caring communities.

Over time, emotional masking can contribute to burnout, emotional numbness, and a sense of detachment from one’s own life.

Privacy Versus Masking

It is important to distinguish between emotional masking and healthy boundaries. Choosing not to share personal feelings is not inherently harmful. Privacy can be empowering when it is based on agency rather than fear.

The difference lies in motivation. Privacy feels intentional and grounded. Masking feels compelled and tense. One preserves energy, while the other consumes it.

For many trans people, the challenge is learning to tell the difference. Years of living in environments where emotional expression carried consequences can make masking feel indistinguishable from self-control.

Recognizing when emotional restraint is no longer necessary is often a gradual process.

Learning to Unmask Safely

Unmasking does not require sudden vulnerability or public disclosure. For most people, it begins quietly, through small acts of honesty in low-risk settings.

This might involve answering a question truthfully with a trusted friend, acknowledging discomfort internally instead of dismissing it, or allowing oneself to feel emotions without immediately analyzing or minimizing them.

For me, unmasking began with noticing patterns in my own language. I realized how often I defaulted to reassurance, even when it was not accurate. Replacing those automatic responses with more honest ones felt uncomfortable at first, but it also felt grounding.

Over time, I learned that not every expression of emotion needs to be justified or explained. Some feelings simply need to be acknowledged.

Why Emotional Masking Persists

Emotional masking does not disappear simply because a person comes out or gains acceptance. Many trans people continue to mask even in supportive environments because the skill has been reinforced for so long.

In some cases, masking remains necessary due to ongoing discrimination or safety concerns. In others, it persists because unmasking feels unfamiliar and vulnerable.

It is also worth noting that not everyone has the same access to safe spaces. For some trans people, masking remains an essential tool rather than a habit that can be easily set aside.

There is no universal timeline or expectation for unmasking. Each person must assess their own circumstances and needs.

Moving Toward Emotional Wholeness

Emotional masking is neither a flaw nor a failure. It is a response to conditions that required adaptability. Recognizing this allows for greater self-compassion.

At the same time, it is worth examining whether masking continues to serve its original purpose. For some, it may still be protective. For others, it may have outlived its usefulness.

Learning to relate to emotions without constant management can be a gradual and non-linear process. It does not mean abandoning boundaries or exposing oneself to harm. It means allowing space for authenticity where possible.

The Bottom Line

Trans people are often described as resilient, but resilience developed under pressure comes with trade-offs. Emotional masking has helped many navigate a world that did not readily make room for them. It has allowed for survival, stability, and adaptation.

However, survival skills are not always compatible with long-term well-being. At some point, many trans people begin to seek something beyond endurance.

Understanding emotional masking is a step toward that shift. It reframes emotional restraint not as a personal deficiency, but as a learned response to structural and social realities.

Living well does not require constant composure. Sometimes it begins with recognizing that it is safe to feel, even quietly, without performance.